- 60-year-old woman

- Ischemic cardiopathy with NSTEMI (11/2024) and PCI of OM1. TTE: LVEF of 60% and moderate primary mitral regurgitation and aortic stenosis

- Diabetic nephropathy with end-stage CKD on chronic haemodialysis via left AVF, with preserved residual diuresis

- CVRF: essential hypertension, T2DM (insulin-dependet), hypercholesterolemia

- Home medication: Clopidogrel 75mg, Asprin 100mg, Atorvastatin 80mg , Nebivolol 5mg, Lecarnidipine 10mg, Doxazosin 4mg, Tamsulosin 0.4mg

- Sudden acute dyspnea and retrosternal chest pain (crushing, rest-related, <20 minutes, recurrent)

- Onset: one day after dialysis (-2.5 kg UF)

- Flu-like symptoms in the previous days

- BP: 190/80 mmHg, HR: 95 bpm, SpO₂: 80%, RR: 25 bpm

- GCS 15/15, normal neurologic exam

- Bilateral fine crackles at lung bases, no peripheral edema. Warm periphery

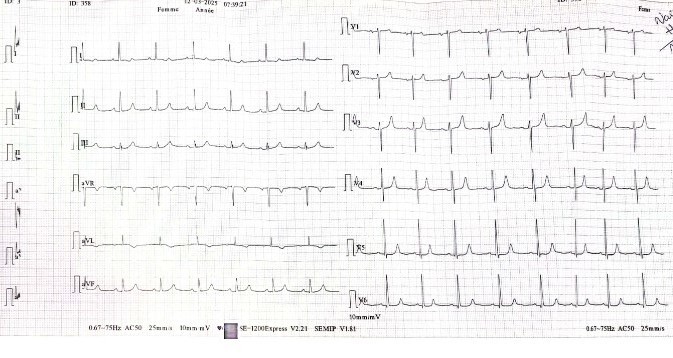

- ECG: Sinus rhythm, normal PQ interval, delayed R wave progression,slight notsignificant ST depression (V3–V6), no significant repolarization abnormalities (unchanged from Nov 2024)

- ABG: pH 7.43, pCO2 33 mmHg, PaO2 41 mmHg, HCO3- 21.9 mmol/L, Lactate 1.5 mmol/L, SaO2 78%

- Significant dynamic increase in hs-Troponin I (from 47 to 503 ng/L); BNP 937 pg/mL

- Na+ 122 mmol/l, K+ 4.6 mmol/L, creatinine 700 µmol/L, urea 20 mmol/L, ALT 10 UI/L, AST 17 UI/L. CRP: 7 mg/L. Glucose: 45.5 mmol/L, HbA1c: 11.7%. Hb 8.4 g/dL, WBC 10⁹/L

Patient Profile

Current Presentation

Clinical Findings

Electrocardiogram

Labs

Chest X-ray

Cardiomegaly, signs of volume over load with redistribution of pulmonary blood flow up to the apices, without pleural effusion.

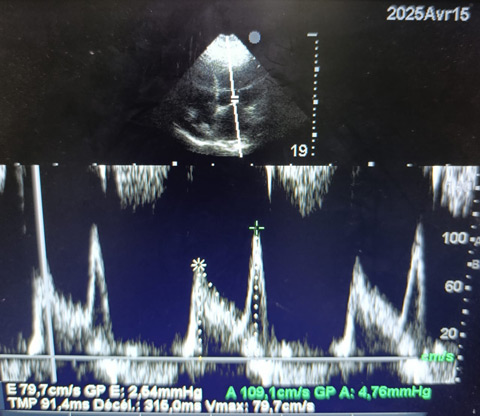

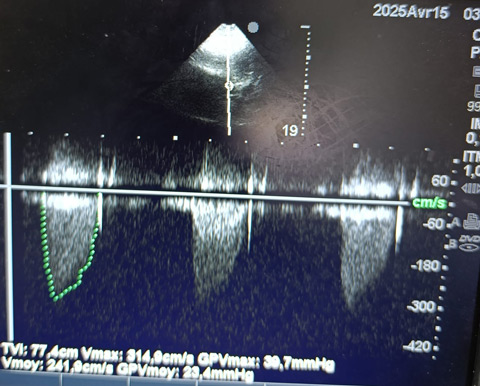

Echocardiography

In general normal LV function with preserved segmental and global wall motion and stable valvulopathy.

Parasternal long-axis view showing left ventricular hypertrophy and aortic valve calcification.

Apical four-chamber view showing a non-dilated left ventricle with preserved ejection fraction, a right ventricle of normal size and function, mildly dilated left atrium, and small pericardial effusion anterior to the right atrium associated with partial diastolic collapse.

Mitral inflow Doppler profile. Pulsed-wave Doppler tracing of transmitral flow showing normal E and A wave velocities (E = 79.7 cm/s; A = 109.1 cm/s), with an E/A ratio <1 and prolonged deceleration time (DT) (316 ms), consistent with impaired relaxation pattern.

Continuous-wave Doppler of the aortic valve showing a mean pressure gradient of 23.4 mmHg, with a mean velocity of 2.4 m/s. These findings are consistent with at moderate aortic stenosis, assuming a normal stroke volume.

- Diagnosis: acute heart failure with nephrogenic pulmonary oedema in the context of acute hypertensive episode and non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction

- Admission subsequently to the ICU

- Initial stabilization with CPAP, nicardipine i.v. and urgent dialysis

- Transfusion of two units of RBC during haemodialysis

- Chronic medications were continued

- Coronaroangiography: moderate new lesion, treated conservatively

- A total of three additional dialysis sessions were performed, with clinical improvement and discharge after seven days

- Optimisation of antihypertensive therapy with ACE inhibitor and follow-up visit scheduled

- Structured diabetes education provided, referral to diabetologist for treatment adjustment

Diagnosis and management

Coronary angiography

Right caudal view showing the left coronary artery, including the left main stem, dividing into the left anterior descending artery (LAD) and the circumflex artery (CX). Diffuse irregularities are observed, with a non-significant proximal CX stenosis. Modest progression compared to one year ago. The image of the right coronary artery is not shown, but it did not reveal any significant lesions.

Follow up

Question 1

✅B. Acute heart failure with nephrogenic pulmonary oedema and non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction

The combination of fluid overload in a dialysis-dependent patient, with a hypertensive peak as a triggering factor, supports the diagnosis of nephrogenic pulmonary oedema.

Coronary angiography excluded any significant progression of coronary artery disease; therefore, the troponin rise is consistent with a type 2 myocardial infarction due to supply–demand mismatch.

Strict control of cardiovascular risk factors is essential not only to prevent coronary artery disease progression but also for effective heart failure management, particularly in HFpEF. In our case, antihypertensive therapy was optimized with an ACE inhibitor and a diabetology follow-up was scheduled, with the aim of initiating an SGLT2 inhibitor. During this visit, a lipid profile—previously unassessed during hospitalization—will also be evaluated.

Regarding heart failure treatment in dialysis patients, available data remain limited, though several promising trials are ongoing. Emerging evidence supports the use of SGLT2 inhibitors in this population and MRA. For further details, see: Khan MS et al. Managing Heart Failure in Patients on Dialysis: State-of-the-Art Review. J Card Fail. 2023 Jan;29(1):87-107 [DOI: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2022.09.013].

Question 2

✅C. Begin oxygen therapy and managment fluid overload

The modality of oxygen delivery should be tailored to the severity of the clinical presentation, with the goal of maintaining oxygen saturation above 90%. In this case, due to respiratory distress and hypoxemia, non-invasive ventilation (NIV) was initiated.

Management of fluid overload requires effective decongestion, typically with diuretics. In dialysis-dependent patients, as in this case, urgent dialysis is needed.

For further details and study material, see: Mebazaa A. et al. Recommendations on pre-hospital and early hospital management of acute heart failure: a consensus paper from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, the European Society of Emergency Medicine and the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17:544–558. [DOI:10.1002/ejhf.289]

Question 3

✅B. Anaemia

Anaemia is common in both HF and CKD patients and is independently associated with reduced exercise capacity, recurrent hospitalizations, and increased mortality. It may also trigger acute heart failure, and ferritin levels should be regularly monitored, in our case, delegated to the nephrology team. In CKD, anaemia often has multifactorial causes, requiring a multidisciplinary approach. Current guidelines do not specify a strict haemoglobin threshold in cardiac patients, but a level of 8 g/dL is generally used to ensure adequate oxygen delivery. For further details, refer to the scientific statement by Beavers et al. on iron deficiency in heart failure (J Card Fail. 2023;29:595–611, DOI 10.1016/j.cardfail.2023.03.025).

HF and CKD: a high-risk intersection

The coexistence of heart failure and chronic kidney disease represents a synergistic risk factor for adverse outcomes, including increased morbidity and mortality. These are independent but pathophysiologically interconnected conditions that require integrated management.Acute HF therapy should be optimized and sustained

Acute heart failure treatment should not be limited to symptom control. Whenever possible, evidence-based therapies (ARNI/ACEi, beta-blockers, MRAs, and SGLT2i) should be initiated or up-titrated early and maintained during and after hospitalization.Comorbidity management is crucial

Careful attention to comorbidities such as diabetes, anemia, hypertension and dyslipidemia is essential in HF patients, as they significantly impact prognosis and guide therapeutic decisions.

Disclaimer

This case report and/or content does not reflect the opinion of iHF or iheartfunction.com, nor does it engage their responsibility.